Blog Layout

FINDING THE SITE THAT INSPIRED THOMSON’S “NORTHERN RIVER” PAINTING

John Gardner • Feb 06, 2020

A discussion paper on Finding the site that Inspired Thomson’s “Northern River” Painting. Observations and proposal by John Olin Gardner, London, Ontario

Below is a photo of the original sketch by Thomson of “Northern River”:

Introduction: Unlocking the secrets of Thomson’s Northern River

2017 marks the 100th anniversary of Tom Thomson’s passing.

The exact site where Tom Thomson’s “Northern River” painting (1915) was inspired and created as a sketch over 36,500 days ago remains a mystery for many. Most now concede that the inspiration for the painting came from a gentle flowing section of the Oxtongue River somewhere on or near the west side of Algonquin Park. I propose that the source and inspiration of one of the most iconic and recognizable paintings ever created by a Canadian landscape painter exists within the current boundaries of Algonquin Provincial Park along the Oxtongue River and on the Whiskey Rapids Trail. The information that follows is a summary of a series of observations that took place in late September 2016 after a trip into Algonquin Park to do some painting and hiking.

My intent in summarizing my findings is to add some clarity to the mystery of “Northern River” from my point of view. The arguments that I make on a number of issues are based on evidence, my experiences as both a plein air artist and as botanist and horticulturist. After my experiences this past fall (2016) I feel a sense of responsibility in sharing my observations, thoughts and hypothesis to the larger community of Tom Thomson followers.

You can decide for yourself.

I would like to acknowledge the wonderful work of those individuals who have documented not only the history of Algonquin Park and its residents and visitors but also the authors of the various books on the life and times of Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. These texts are an indispensable resource for anyone exploring the life and times of TT and his colleagues. I have listed a selection of references at the end of this document.

Hiking in Algonquin Park 2016

In late September 2016, while hiking in the Park with my wife Paula, we stumbled onto a site in the west end of Algonquin Provincial Park that was shockingly familiar in so many ways. It took me a while to connect the dots and form a hypothesis about what I was looking at. This site was on a high bank or bluff overlooking a gentle flowing section of the Oxtongue River as it made a quiet turn and essentially disappeared from view.

The angle and position where we stood that day, gave me a view that was eerily so similar in terms of the “look and feel” of the painting “s” done by Tom Thomson entitled “Northern River” that I am having difficulty getting past what I saw and felt that day. There are dozens of twists and turns in the Oxtongue River but this site was different somehow. It spoke to me and everything about it seemed “right”.

While standing on that bluff after a few minutes, I started feeling an overwhelming sense of familiarity or “déjà vu” as though I had seen this landscape before.

I was looking through a loose screen of spruce elevated above the Oxtongue River to a shoreline with the same geometry and colour of water at the edge of the river as the “Northern River” painting (Figures 1d,7.).

It dawned on me then, this must be where Thomson stood when he first saw his “Northern River” painting in his mind. This landscape shown in my photos has the same look and feel to me as the landscape represented in the painting(s) done by TT entitled “Northern River”.

More than a 100 years have gone by since Thomson stood up from the river on this bluff, I believe, looked down and sketched his iconic view through a loose screen of black spruce. What has not changed is the geometry of curvature in the river and the mix of vegetation as it relates to the soils (poorly drained) and river ecology. Some of the living trees and deadfalls looked pretty old for black spruce and could have been some of the same trees Thomson looked at in the fall of 1914.

As far as I know, up to October 2016, no one had ever proposed or made a connection between what is there today for all to see and the probability that this could be the exact location where TT was inspired to paint his “Northern River” sketch.

I feel comfortable from what I can conclude in initiating a discussion on the degree of probability that this site is where TT felt inspired and executed his first sketch for Northern River. There are too many coincidences to make me think otherwise. Has this site been in plain view all along?

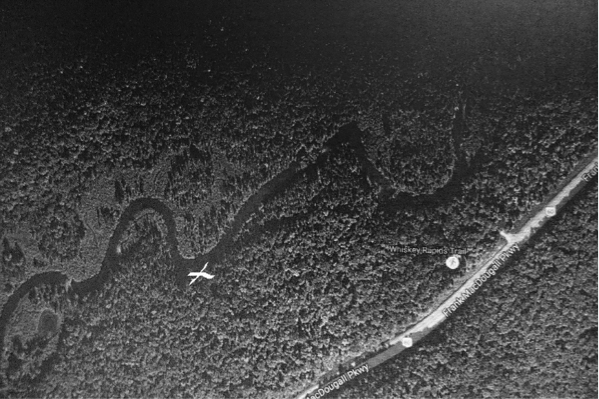

This view is from a low-rising bluff on the south side of the Oxtongue River looking north along the Whiskey Rapids Trail taken late September 2016. See the cropped portion of the Google Earth map below (Figure 8.).

I have attached a couple of photos of that location looking north as it appears today (Figures 1a and 1b).

On the trip this year into Algonquin Park, our intent was entirely on sketching, hiking and cycling. I wasn’t looking for anything in particular. I did recall from hiking on the Whiskey Rapids Trail a few years ago how wonderfully well the afternoon light spilled across the valley floor and onto the opposite side of the Oxtongue River looking north. This memory is what brought us back to the trail for a hike and the possibility of a quick plein air oil sketch not knowing what sequence of events would occur on that afternoon in late September 2016.

For many years, I had been vaguely aware of the controversy about where the “Northern River” was first sketched by Thompson but had never studied the issue until the fall of 2016. I had been on this trail before but for some reason, this time, everything connected.

As far as I knew in late September 2016 nobody really could tell anyone exactly where “Northern River” was inspired even though there existed a variety of possibilities backed by anecdotal information and popular opinion. At this time, I did not know about the plaque commemorating TT and “Northern River” on the lower reaches of the Oxtongue River. I have never been at any of the “said” locations.

Historically, other TT researchers have been looking for evidence of a “swamp “at the site based on Thomson’s comment about his “ swamp” painting, which I would consider to be a “red herring”. I will expand on this later in the discussion. There are I am sure hundreds of sites in and around Algonquin Park that have some of the elements obvious in the painting.

The site in my proposal not only includes all those elements but they are all in the right place in relation to each other.

The Landscape and its Trees along the Oxtongue River

On the Whiskey Rapids hike, we took our time and enjoyed the day (I spent some time fishing) as it was sunny with some cloud and ideal for hiking and generally exploring. We arrived at a location that is not too far from the head of the trail where a steep bank or bluff rises from the Oxtongue River on the south side. The river then gently turns away and disappears behind a visual screen of flora that is dominated by black spruce but also included alder, and a variety of deciduous trees including some maple in the distance on higher ground with chaparral dominant here and there filling space.

Black spruce on that bluff (right of center in photo 1b) where I believe TT was inspired to create “Northern River”

Notice how these spruce have grown with a curvature that is similar to Thomson’s curved spruce in his painting. These spruce are exhibiting what botanists called a “tropism”. These spruce trees are attempting to orient themselves in a more vertical position for best growth. Notice how the black spruce across the river are full and lush being in better light (Figure 1c.).

The Bluff

High up on this bluff (maybe 15 or 20 ft. above the water’s surface), there is an assortment of black spruce of differing ages and shapes. I noticed some were curved upwards and most more or less straight as an arrow. You could see that the further away you stood from the edge of the bluff, the black spruce was rooted much stronger. The trees that were 30 or 40 feet back from the edge of the bank were much larger and stronger as the soils changed to hold more of a mix that included hardwoods.

Some trees were dead, dying, wind thrown or slanted and some without very much foliage. Others appeared in a juvenile state, quite healthy and growing well near the edge of the bluff. I stopped here and said to my wife Paula, “Whoa -This would be a great spot to do a painting”. This was after I enjoyed looking at the trees on top of the bluff and how they related to the view across the valley and before I formulated any opinions about what we were looking at. It was also a few minutes before I really started to think about what I was looking at in a much broader perspective. Up to this point, like all hikers we had been concentrating on our footsteps and balance as we moved along the trail.

One of the most remarkable set of trees there today are curved the same way Thomson’s curved spruce flows up through the center of his painting Northern River.

This apparently is the way some of the spruce grow in this location. They grow outwards from the bank and then upwards making a nice curve (see Figure 1c).

Black spruce is moderately shade tolerant. The tree will bend for optimal orientation with regard to gravitational forces and the best light if necessary to improve its chances for survival and longevity. The orientation of these curved trees, is similar to the black spruce in the center of the “Northern River” painting. That curved spruce echoes the curve in the river. Thomson’s intention of representing that single tree was no mistake. It makes a strong composition more forceful. Thomson used diagonal shapes and lines better than most plein air artists. Curiously, there are other spruce in this same clump (Figure 1b – right of center) of trees today that are growing straight up giving the impression that in a few decades, this grouping of trees will look very close to the ones that form the screen of trees in the foreground of the “Northern River” painting.

What the painting “Northern River” Reveals…

The hidden clues (Figure 1d.)

Northern River by Tom Thomson 1915 oil on canvas 45×40 inches

One of the most distinguishing features I see in the original work is that the artist Thomson appears to be looking down onto the surface of the water and into the river rather than more or less across it (Figures 3, 5.).

I would conclude that TT must have been standing in an elevated position above the river rather than standing on its floodplain or just up from its surface. Other locations down river from Ragged Falls would have put Thomson more or less level with the surface of the river. Black spruce is the predominant tree in the painting. We know it as a smallish conifer on wetter soils and sites. In the painting, the reflection of the tree trunks from the opposite side of the river stretch across the river to the near shore. I would venture to conclude that the width of the river is relatively narrow (See Figures 3). I would estimate the rivers’ width at this location to be 40 – 45 feet wide without measuring. This is in comparison to some stretches of the Oxtongue River that are much further downstream and well on the other side of Ragged Falls. The width of the river downstream can be expansive and in my estimation twice the width of the river as it flows next to the Whiskey Rapids Trail at my proposed site.

I believe the painter Thomson was facing north with his back to a fairly dense woodland since the growth of the black spruce screen appears thin and light starved. Black spruce does tolerate shade and can grow in the shade but has a different look than black spruce growing in full sunlight.

The incoming sunlight appears to be more or less filtered out by a relatively dense forest canopy behind the artist and the screen of spruce in the original sketch. The trees in the foreground of the sketch “Northern River” are weak growing black spruce. This tells me that the environment in which these trees had developed was no better than an adequately supplied with light and soil factors.

Thomson’s Algonquin neighbourhood in the early 1900’s

If one studies the history of Algonquin National Park when its boundaries were recognized in 1893 with an official map, you get a clearer image of roads, timber rights, railway lines as well as known names of various lakes and waterways. Back then, Oxtongue Lake carried the same name as it does today.

The river we now refer to as The Oxtongue River was then called “North River” as seen on the 1893 map (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algonquin_Provincial_Park). This name is probably the one Thomson used to describe this waterway. The site that I believe where Thomson got his inspiration to paint “Northern River” appears to be inside and near the edge of the Park boundaries established in 1893.From what I can see, there were no means of accessing this site directly 100 years ago other than by foot or with relative ease by canoe from the lower side of Tea Lake Dam.

The Oxtongue River known as the “North River” in the early 1900’s just above Ragged Falls and before the river gains considerable flow volume and widens as seen in photos of the lower reaches of the Oxtongue River. The site represented in the painting above is down river from Whiskey Rapids and the bluff where I feel Thomson got his inspiration for “Northern River”.

The painting in Figure 2. A 12×12 plein air oil by John Olin Gardner (Sept. 2016).

View Looking east up the Oxtongue River and towards Tea Lake Dam. Thomson would have looked across (northerly) and downwards (see arrows) into the river and onto the water’s surface from a position on top of this steep bank on what we now call the Whiskey Rapids Trail. Here you can get a feel for the width of the Oxtongue River near this steep bank or “bluff”. This location is a relatively short and easy canoe trip from the lower side of Tea Lake Dam.

As a painter I have had many painting excursions into Algonquin Park and the near ‘North Country’ over the last two decades. In the painting that follows (Figure 4), you can see a mix of both deciduous and coniferous trees and shrubs with the skeletons (right of center in the painting) of dead black spruce showing where poorly drained soils have been turned into soils that don’t drain at all. These soils now stay wet year round. At one time, they supported healthy black spruce before soil drainage patterns were changed along road ways in and around Algonquin Park.

An 11×14 plein air oil entitled “Near Ragged Falls” painted in late September 2016 by John Olin Gardner. Ragged Falls appears to be a benchmark landscape feature in discussions about the Oxtongue River.

Locations are either above or below the “Falls”. The above plein air oil Figure 4 is a good representation of John’s work as a plein air artist and student of the northern landscape. John has enjoyed interpreting and representing the Canadian landscape with paint and canvas for many decades.

What other Thomson historians and authors have said about the origins of “Northern River”.

One would think that with the number of words in print and now on video, about Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven that there would be little else that’s new and available to say. I have collected many fine texts written by numerous authors describing the life and times of TT. As well, there are now great videos on this subject material. When referencing the “Northern River” paintings, opinions have differed widely as to where its inspiration came from and whether or not this inspiration was from an actual site or if it was something that TT dreamed up in his Toronto studio during the winter of 1914-15. I am going to suggest that the composition of this painting is far too complex, original and different than anything else he did to have conjured it up without having seen and sketched at an actual site. I believe the painting represents the signature “feel and look” of a work done by a very accomplished plein air artist from an actual site. I find it hard to believe as an experienced plein air artist myself that Thomson wouldn’t be tempted to do some sort of a sketch on site even if it was in graphite and equally hard to believe that “Northern River” is something that he put together by fumbling around in a studio until he got it right. Furthermore, I believe Thomson did not “dream up” that curved spruce running up through the center of his painting (Figure 1c.) that more or less echoes the “curve” in the river. Trees with the same shape and growth habit exist today in the same spot where I believe Thomson stood over 100 years ago.

Black Spruce- A key to unraveling the mystery of Northern River – Thomson’s “swamp picture”

It’s almost impossible not to see black spruce in the North Country simply because of its dispersion in Canada (Nova Scotia to British Columbia) and the fact that it does well on imperfectly drained soils. These soils comprise or make up most of the “land “in Canada. Black spruce is considered to be a slow growing wetland tree found across the country. The black spruce is also considered to be a transcontinental North American tree. Black spruce historically has been called “swamp spruce” and/or “bog spruce” because of its adaptive qualities on soils that are considered to be wet and slow draining compared to free draining Class A agricultural soils found in Southern Ontario that have few limitations for crop production. This species of conifer is to be found all along the Oxtongue River on both sides of its banks. Check out a close-up of the river on Google Earth.

Black spruce as a wood has an excellent strength to weight ratio. It is quite stiff and very light. This tree can live up to 200 years and is shallow rooted. This allows it to survive in and on the “top layer of poorly drained soils” where a high water table exits. Because of a limited root system, the tree is subject to wind throw. It doesn’t take much to knock a small poorly anchored black spruce out of the ground. This would explain the presence of numerous tree skeletons floating in the Oxtongue River and scattered along its shoreline. One could also speculate that some of the oldest living trees showing in my current photos (Figure. 6) taken in 2016 and on the site today could be the same ones Thomson looked at 100 years ago when they had been growing for only a few decades.

Where I believe Tom Thomson stood to sketch “Northern River”.

Black Spruce along the Oxtongue 36×40 acrylic on canvas by John Olin Gardner

Another view from the bluff looking north as it is today

TT’s Northern River sketch painted around 100 years ago.

I believe the large black spruce in figure 6 on the left side of the photo in the foreground is the same black spruce that appears on the left side of the sketch “Northern River”.

The Physical Location within Algonquin Park

The location today is also ecologically fragile in my opinion and cannot sustain more volume of traffic than it now has along the Park trail. See Figure 8.

A cropped section of the Google Earth Map. X marks the spot where I believe TT stood and first saw his “Northern River”. This spot on the “Whiskey Rapids Trail” would have been a gentle canoe ride for Thomson from the lower side of Tea Lake Dam where Thomson fished frequently.

Tom Thomson I believe stood within inches of the existing trail and looked through a screen of trees in the same spot where their descendants now stand. (See Figures 3, 5.).

I would also suggest that this location appears to be a relatively easy canoe trip down the Oxtongue River from the lower side of Tea Lake Dam and well within Thomson’s Algonquin neighborhood.

One main reason I believe that this site could be considered as the location where TT painted from, is that the geometry, shape and location of key markers in the landscape (when viewed from the top of the river bank or bluff) on the site as it is today, fit more or less precisely as an overlay with the shoreline as it is today matching perfectly over the painting “Northern River” when brought into a similar scale of size (my photo vs the actual painting) when viewed from the top of the bluff at eye level. (See Figures 6, 7.)

I would maintain that the outstanding criteria for site location has to be a reasonably close match of woody plant materials and river curvature when seen from a standing position. The river has to be sufficiently narrow for the reflection of the smallish black spruce to reach from shore to shore. I am also convinced the painting “Northern River” was done in a position along the Oxtongue River that has an “intimate” feeling and where the river can be seen from an elevated position looking more or less down onto its surface and into the more shallow sections of the river along its shoreline.

Thomson’s Swamp Picture

The one piece of information that appears to cloud the issue of where this painting was done and what inspired it, is Tom Thomson’s comment to his nephew about his “swamp picture” being “not half bad”. By using the word “swamp” I believe it has confused and misled Thomson historians and researchers for decades.

It appears evident to me that anyone taking this comment literally as a clue when searching for a probable site would be looking for, a “swamp” in the landscape even though there is no indication of what I would call a swamp in any of the paintings entitled “Northern River “nor in my accompanying photos. The painting “Northern River“ is a painting about a river and its ecology, not a painting of a swamp.

The only readily identifiable tree in the painting “Northern River” is black spruce. When I think of swamp, I think of cat tails, willow species and various sedges etc. growing over an area or proximal to an area that stays more or less wet year round. A “swamp” in my mind would be an area that collects water and for all practical purposes doesn’t allow for any drainage.

What most folks don’t know is that Black Spruce as we know it as a wetland tree, would have likely been called “Swamp Spruce” in the days when Thomson was living and when he painted “Northern River”. Current reference literature tells us that Black Spruce has 2 other common names. The accepted common names for Black Spruce, are “swamp” or “bog” spruce. This tree is a wetland tree but does not survive in a location where water stands year round i.e. in a swamp. Could it be that Thomson was describing the overall landscape in his “Northern River” in an overly simplified way by calling it his “swamp picture” because the tree that he saw in the landscape that was totally dominant along the river bank was “swamp spruce”? Thomson was known to be rather quiet and somewhat short when it came to talking.

This colloquial talk with his nephew, I believe, was based on his understanding of “swamp spruce” and where it could be found. We must remember that Thomson had a youth spent in Grey County where land too wet to plow and crop could easily be referred to as “swampy” in a casual conversation. The range of Black Spruce in southern Ontario extends into both Bruce and Grey counties where Thomson was raised.

Concluding Remarks

Although no absolute proof or eye witness accounts exist as to where Thomson was first inspired by the Oxtongue River to create his “Northern River”, there are several convincing clues in the painting and at this proposed site on top of the river bank on the Whiskey Rapids Trail. The strongest of which is the look and feel of the site and its physical match to the actual painting. No one expects the site to look exactly as it did 100 years ago, however the shoreline geometry and general shape of the landscape with accompanying tree cover has remained more or less the same today as it did 100 years ago at the Whiskey Rapids location. My intent with this document is to present a viewpoint and evidence to support the proposal that the site where Tom Thomson was inspired to paint Northern River remains much the way it looked one hundred years ago and is located within the boundaries of Algonquin Provincial Park as it is today. Judge for yourself.

Written by: John Olin Gardner, London, Ontario

Background on the author of this article

John is a plein air artist (Figure 9) living in London, Ontario with 40 years of painting history (field and studio). He has a strong background in both Botanical Science and Horticulture Science with degrees at the undergraduate and post graduate level from McGill University (MacDonald campus) and University of Guelph. He has worked in agricultural sciences for more than 35 years. Over the years, he has authored dozens of popular and scientific articles and reference materials for agriculture and horticulture science. One of John’s lifelong interests has always been in the study of woody plant materials, tree physiology and adaptive qualities of various trees found in our temperate climate. John was born in 1951 in Nova Scotia and has lived and painted in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec and Ontario. His lifelong connection to the landscape started as a boy camping and fishing. He completed his first oil painting at age 7.

John Olin Gardner painting in Sept. 2016 Killarney, Ontario. Photo courtesy of photographer Rob Stimpson of Huntsville, Ontario.

Bend in the Oxtongue River 36×36 acrylic/c by John Olin Gardner 2016.

References and Links

- Clemson, Gaye Isabel (2006). Treasuring Algonquin 2006. Trafford Publishing, Victoria, B.C., Canada.

- Davies, Blodwen (1935). Tom Thomson. Discus Press.

- Farrar, John Laird (1995). Trees in Canada. Fitzhenry & Whiteside, Ltd. And the Canadian Forest Service, Natural Resources, Canada.

- Hill, Charles C. and Reid, Dennis (2002). Tom Thomson. Art Gallery of Ontario, National Gallery of Canada, Douglas and McIntyre, Vancouver, B.C., Canada.

- Hozer, Michele and Raymont, Peter (2012). West Wind. A documentary film. Produced by White Pine Pictures, www.whitepinepictures.com.

- Murray, Joan (l986). The Best of Tom Thomson. Hurtig Publishers, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

- Murray, Joan (l999). Trees/Tom Thomson. McArthur and Company, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- Murray, Joan (2011). A Treasury of Tom Thomson. Douglas and McIntyre, Vancouver, Toronto, Canada and Berkeley.

- Saunders, Audrey (1951). Algonquin Story. Department of Lands and Forests, Ontario, Canada.

- Silcox, David, P. (2003). The Group of Seven and Tom Thomson. Firefly Books, Ltd., Willowdale, Ontario, Canada.

- Town, Harold and Silcox, David, P. (2001). Tom Thomson, The Silence and the Storm, Firefly Books, Ltd., Willowdale, Ontario, Canada.

- Waddington, Jim and Sue (2013). In the Footsteps of the Group of Seven. Goose Lane Editions, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada and Art Gallery of Sudbury, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada.

- http://www.damnyak.ca/2011/10/along-trail-in-algonquin-park-with.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algonquin_Provincial_Park

By John Gardner

•

19 Feb, 2020

This is the number one question I get when I’m displaying my work. The truth is that for most paintings like small plein air panels, the answer is “not very long”. Understandably it does require an absolutely dedicated period of time based on a skill set I started to develop as a 7 year old and continue to this day. This skill set is still a work in progress after 60 years! A painting can take anywhere from a half hour to days and even years for some really large pieces before some are finished. The preparation and cleanup can take longer to execute than doing a small plein air panel. If I try to explain what is behind each painting by quantifying time, costs and frustration it may be easier to visualize what I’m talking about. When you get the best from a working artist, you get the experience that years of trial and error can teach. For me, in the last 20 years, I have probably gone through 100 K of paint, brushes, canvas, easels, and boxes, not to mention the cost of frames where I have used them. Artists have a tendency to be quite mobile and can use up a vehicle in a few years if they travel to a lot of shows, venues as well as travel to art shops and other suppliers where all the tools of the trade can be found. I probably have around 15,000 hours in painting and its related activities over the last 10 years. I have been fortunate enough to have been collected by clients from around the globe. This makes my efforts worthwhile. I am very grateful. I hope this short commentary helps clarify some of the basic questions about the elements and effort that are behind each and every painting.

By John Gardner

•

12 Feb, 2020

Assuming the painting was produced using the finest oils and pigments, there is really little to do but enjoy the work. The most common concern for new collectors is light exposure in excess. High quality oils and acrylics are made of light-fast pigments which have been rigorously tested for colour longevity. Under average room conditions there is little concern. Typically oils and acrylics do not require glass for showing. I would however, recommend avoiding temperature and humidity extremes. Occasional surface dusting can help. Most oils and acrylics are varnished with a protective finish that will help maintain colour chroma for a lifetime of enjoyment. When transporting a work, make sure there are no pressure points against the canvas.

By John Gardner

•

06 Feb, 2020

Years ago I experimented with a French easel which was beautifully designed and made but I found it too heavy and cumbersome. I eventually made several plein air box prototypes based on what I thought I would work until I refined the product down to an 8 ½” x 10 ½” (internal dimensions) box that would hold a palette and one panel the same size. The box weighs around one pound without any paint. I usually preload the palette with enough paint to cover the selected panel size for the day. This box is made from white cedar and Baltic birch plywood and reinforced with fiberglass. It has an insert nut that allows it to be mounted on a tripod. The panel can be clipped to the box lid when it is hinged up in an upright position or held separately. My field pack usually weighs much less than l0 lbs. and both hands are usually free while hiking to a location. I like to carry a walking staff set up to accommodate an umbrella.

By John Gardner

•

06 Feb, 2020

If you’re fortunate enough to be able to stick with a routine or process long enough at some point pieces start to look like they came from the same set of hands. Maybe it’s the recognizable stroke or brush work. It could also be a recognized palette of colours that work really well together. I have found that a limited palette of colours can produce more satisfactory results than trying to use too many different pigments. Subject material can also help collectors recognize an artist’s hand. I prefer mostly landscape painting and do enjoy some figurative work and occasionally use abstracts to work ‘outside the box’. I have always relished the act of experimentation with both process and materials. Currently I apply paint with brush, knife and fingertip…whatever feels right for the moment. The brand is more than the product alone. The brand includes the people behind the product, their integrity, delivery, availability, pricing structure, etc. Ultimately, you’ll know a good painting when you see it!